Gut Permeability and Metabolic Endotoxemia

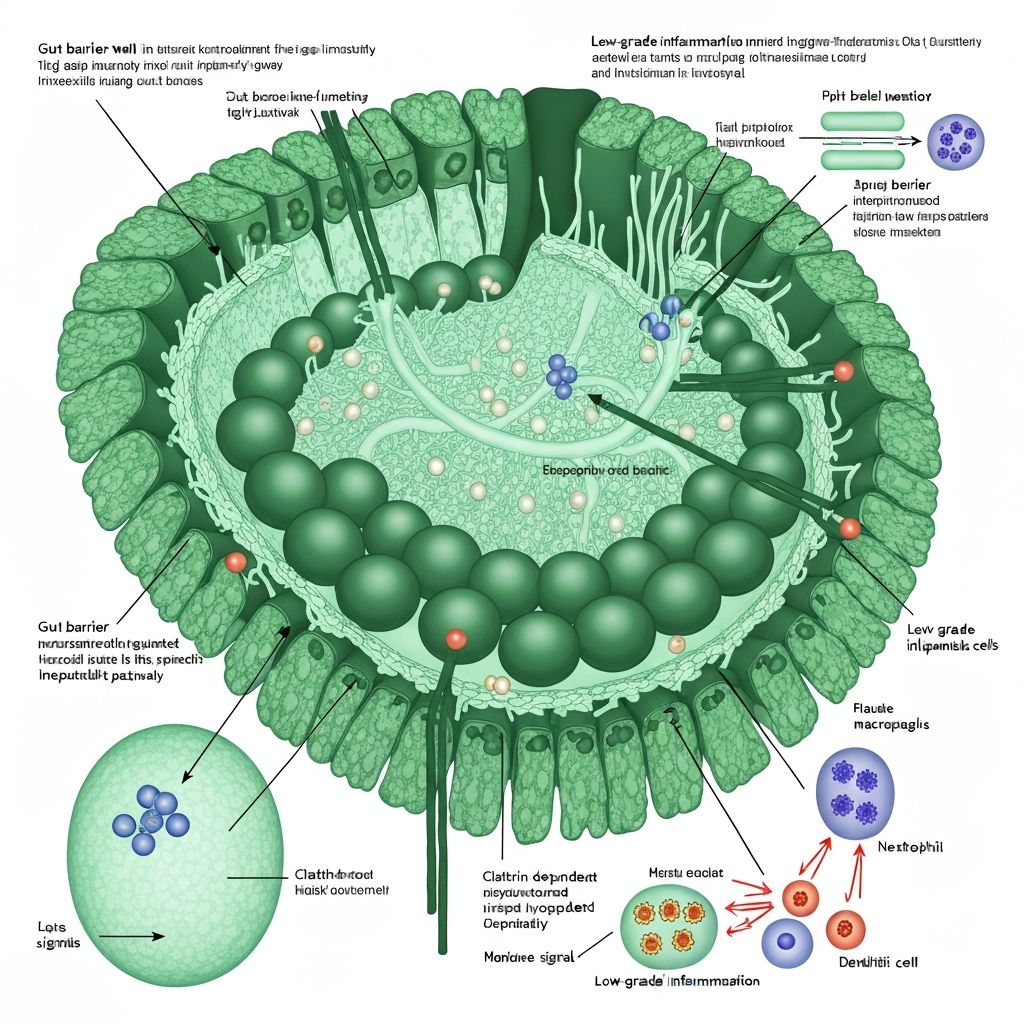

The intestinal epithelium serves as a selective barrier separating the luminal environment (containing trillions of microorganisms and their metabolites) from the sterile internal milieu. This barrier function is maintained through multiple mechanisms, including tight junction proteins, the mucus layer, antimicrobial peptides, and the intestinal immune system. Dysbiosis and altered microbiota metabolite production can compromise this barrier, leading to increased paracellular permeability and translocation of bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) into the portal circulation—a condition termed "metabolic endotoxemia."

Intestinal Barrier Structure and Function

The intestinal epithelium is lined by a single layer of columnar epithelial cells joined by tight junctions composed of claudins, occludin, and zonula occludens proteins (ZO-1, ZO-2, ZO-3). These proteins form a paracellular pathway, regulating ion and water transport whilst restricting passage of large molecules and bacterial antigens. The mucus layer, produced by goblet cells and reinforced by mucin-degrading bacterial species (particularly Akkermansia muciniphila), provides a physical and chemical barrier.

The intestinal immune system, including intraepithelial lymphocytes, lamina propria immune cells, and Peyer's patches, actively tolerates commensal microbiota whilst defending against pathogens. This immune homeostasis depends on signalling from microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) and metabolites like short-chain fatty acids.

Tight Junction Integrity and Dysbiosis

Dysbiotic microbiota are characterised by reduced abundance of beneficial bacteria, including SCFA producers and mucin-supporting species. This dysbiosis impairs barrier function through multiple mechanisms:

Reduced SCFA production: Butyrate reinforces tight junction protein expression and colonocyte metabolism, supporting epithelial integrity. Dysbiosis-associated reduction in SCFA production diminishes this protective effect, allowing increased paracellular permeability.

Mucus layer degradation: Dysbiotic communities often lack Akkermansia and other mucin-degrading commensals, resulting in a compromised mucus barrier.

Pro-inflammatory signals: Dysbiotic communities enriched in Proteobacteria and other gram-negative species produce higher quantities of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), triggering toll-like receptor (TLR) signalling on epithelial and immune cells.

Altered zonulin expression: Zonulin, a tight junction regulator, is increased in dysbiotic states and in response to dysbiosis-associated antigens, promoting temporary paracellular opening. Elevated zonulin is associated with increased intestinal permeability across populations.

Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and Endotoxemia

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a gram-negative bacterial cell wall component composed of a lipid A moiety embedded in the outer membrane and a polysaccharide O antigen. LPS is recognized by toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and is a potent trigger of innate immune activation.

In healthy individuals, systemic LPS levels are maintained at low concentrations through intestinal barrier exclusion. However, dysbiosis-associated increased LPS production combined with increased epithelial permeability allows LPS translocation across the intestinal barrier into portal blood. This phenomenon, termed "metabolic endotoxemia," represents a state of chronic systemic exposure to low-grade LPS concentrations—distinct from acute endotoxemia but sufficient to trigger persistent pro-inflammatory signalling.

Metabolic Consequences of Endotoxemia

Circulating LPS activates TLR4 on immune cells, adipocytes, hepatocytes, and other tissues, triggering production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. This systemic inflammation impairs metabolic homeostasis through multiple mechanisms:

Insulin resistance: Pro-inflammatory cytokines inhibit insulin signalling through JNK and IKK activation, impairing glucose uptake in muscle and adipose tissue.

Hepatic inflammation: Portal LPS and inflammatory cytokines trigger hepatic inflammation, impairing the liver's role in glucose production and lipid metabolism regulation.

Adipose tissue dysfunction: Systemic inflammation activates innate immune responses within adipose tissue, promoting macrophage infiltration and impaired adipocyte metabolism.

Appetite dysregulation: Systemic inflammation interferes with satiety hormone signalling, potentially promoting dysregulated energy intake.

Research Evidence in Obesity Models

Rodent obesity studies demonstrate that dysbiosis-associated LPS translocation precedes weight gain. Germ-free mice colonised with dysbiotic microbiota develop rapid weight gain, increased intestinal permeability, and elevated systemic LPS. Similarly, selective antibiotic depletion of SCFA producers increases intestinal permeability and LPS translocation in obese animals.

In humans, elevated circulating LPS concentrations correlate with markers of obesity and insulin resistance in some (though not all) studies. Individuals with elevated LPS levels exhibit increased systemic inflammation, impaired glucose homeostasis, and reduced insulin sensitivity compared to those with low LPS levels. Weight loss is accompanied by decreased circulating LPS and systemic inflammation, though these changes correlate only modestly with metabolic improvements.

SCFA's Protective Role

The protective effects of SCFA on intestinal barrier integrity are increasingly well-characterised. Butyrate promotes tight junction protein expression and colonocyte metabolism, increasing epithelial barrier function. This mechanism explains why fibre-rich diets and SCFA-producing-bacteria-enriched microbiota maintain low intestinal permeability and reduced LPS translocation, even in obesity-susceptible individuals.

Limitations and Unresolved Questions

Whilst evidence supports a link between dysbiosis, increased intestinal permeability, LPS translocation, and systemic inflammation, key causal questions remain incompletely resolved. Directionality is ambiguous: does dysbiosis-driven LPS translocation cause weight gain and metabolic dysfunction, or do obesity and dysregulated metabolism trigger dysbiosis, altered epithelial permeability, and secondary LPS translocation?

Most evidence derives from rodent models; direct causal evidence in humans is limited. Cross-sectional studies show correlations but cannot establish causality. Interventional trials targeting dysbiosis to reduce LPS translocation and improve metabolic health are few and show variable results.

The clinical significance of modest elevations in circulating LPS remains uncertain. Many obese individuals exhibit normal LPS levels, and many lean individuals show elevated LPS, suggesting that LPS translocation is neither necessary nor sufficient to explain obesity or metabolic dysfunction in all individuals.