Gut Microbiota Composition and Body Weight Regulation

An exploration of evidence-based associations between microbial communities and metabolic processes

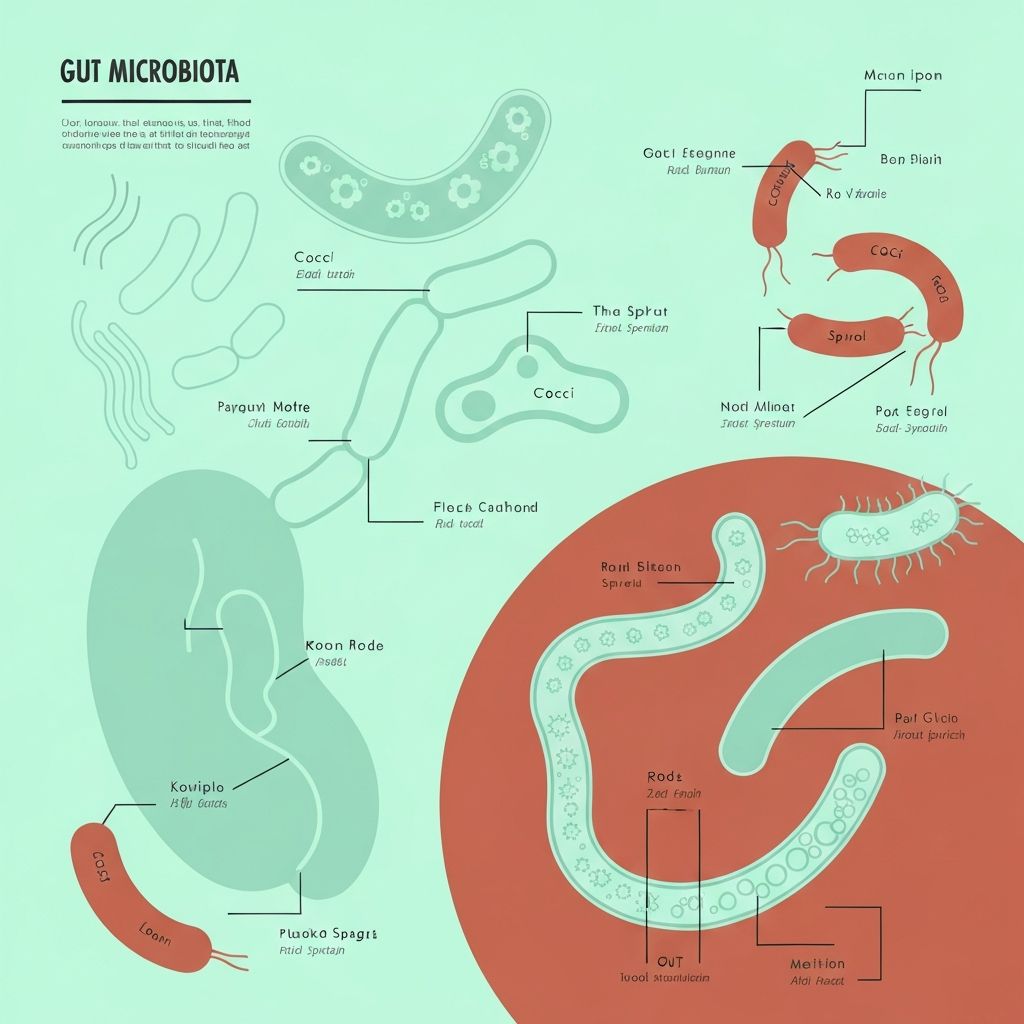

Introduction to Gut Microbiota Basics

The human gastrointestinal tract harbours a complex community of microorganisms—bacteria, archaea, viruses, and fungi—collectively termed the microbiota. This ecosystem comprises trillions of cells, with bacterial species numbering in the hundreds. The composition of this microbial community varies among individuals and is shaped by genetics, diet, antibiotic exposure, and environmental factors.

The primary metabolic function of the gut microbiota involves the fermentation of dietary substrates that escape digestion in the small intestine, notably dietary fibre and resistant starch. This anaerobic fermentation generates metabolically active compounds that influence both local intestinal homeostasis and systemic metabolism.

Short-Chain Fatty Acids Production

The primary end-products of bacterial fermentation are short-chain fatty acids (SCFA): acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These molecules account for approximately 5–15% of daily energy intake in humans and play crucial roles in energy metabolism.

Butyrate serves as the preferred fuel for colonocytes, strengthening the intestinal epithelial barrier and modulating local immune responses. Propionate and acetate are absorbed into the portal circulation, influencing hepatic metabolism and peripheral glucose homeostasis. The molar ratio of these SCFA varies depending on dietary composition and microbial community structure.

The production of SCFA depends on the availability of fermentable substrate and the enzymatic capacity of the microbial community. Fibre-rich diets, particularly those containing soluble fibres and polyphenols, promote elevated SCFA production and may alter the relative abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria.

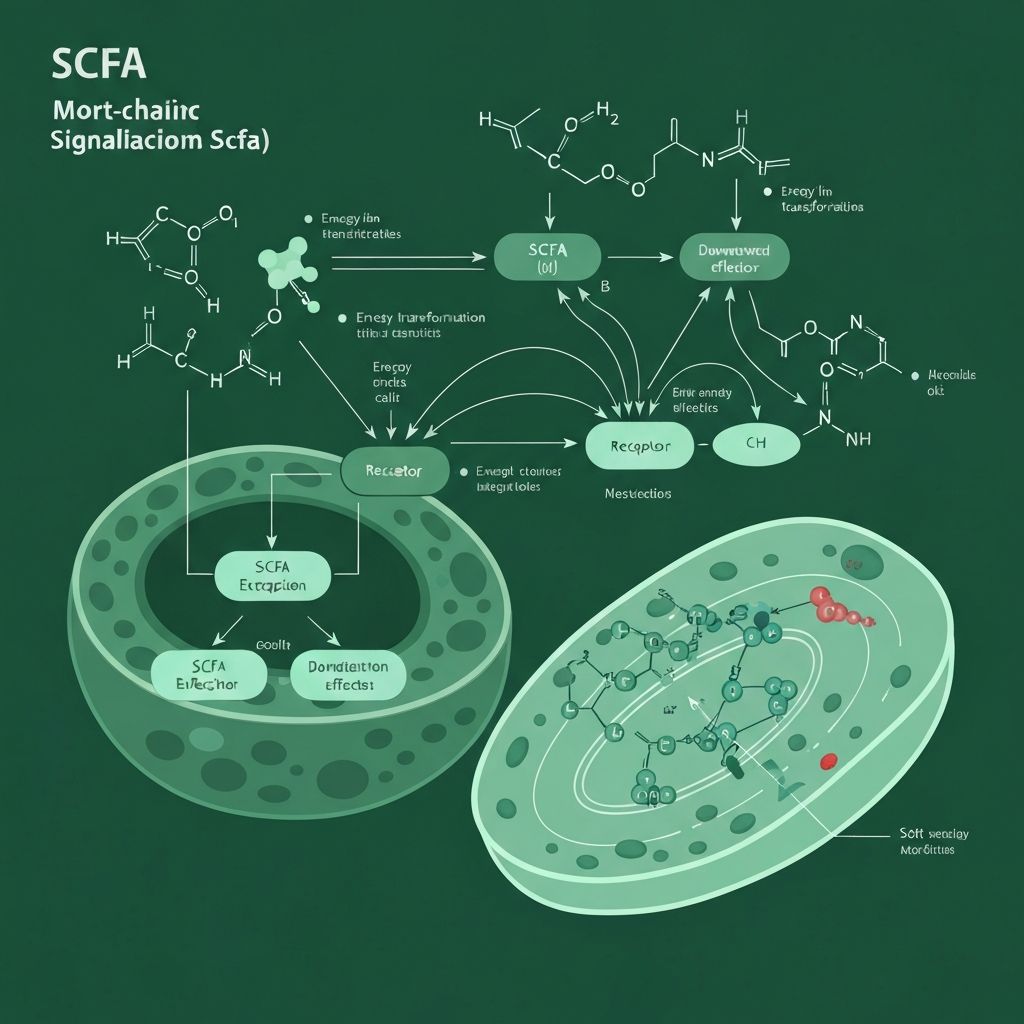

SCFA Signaling to Host Metabolism

Beyond their role as fuel substrates, SCFA function as signalling molecules through several mechanisms. They activate G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) located on intestinal epithelial cells and immune cells, triggering cascades that influence intestinal barrier integrity and inflammatory responses.

At the level of appetite regulation, SCFA signalling modulates the secretion of gut hormones including glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY), which regulate satiety and energy intake. The vagal afferent signalling pathway also transmits microbial metabolite-derived signals to the brainstem, influencing hypothalamic energy homeostasis centres.

Evidence from rodent models and preliminary human studies suggests that variations in SCFA production capacity and SCFA-receptor expression may contribute to interindividual differences in metabolic efficiency and energy expenditure.

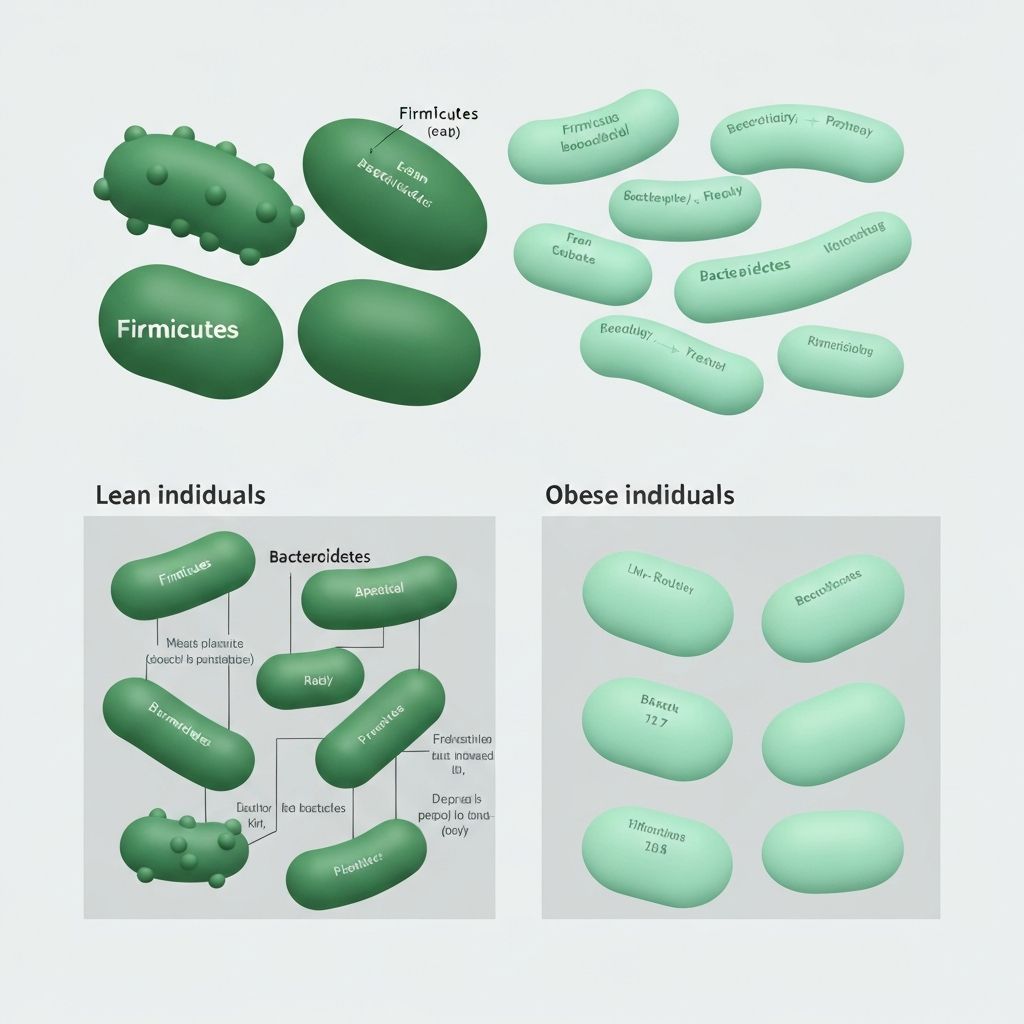

Observed Microbiota Patterns in Body Weight

Cross-sectional studies have reported differences in microbial composition between individuals of differing body weights. One frequently cited observation concerns the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes (F/B ratio), with some studies reporting elevated Firmicutes abundance in obese populations relative to lean controls.

However, this finding is inconsistent across studies, and the ecological and metabolic significance of this ratio remains debated. Other phylogenetic markers associated with body weight variation include reduced bacterial richness and diversity, and altered abundance of specific operational taxonomic units (OTUs) within phyla such as Akkermansia, Faecalibacterium, and Roseburia.

These observational associations suggest that body weight and microbial composition co-vary, though causality cannot be inferred from cross-sectional data alone. Longitudinal studies demonstrate that weight loss is accompanied by shifts in microbial community structure, but whether microbial changes drive weight loss or result from altered dietary patterns and host physiology remains under investigation.

Gut Permeability and Low-Grade Inflammation

The intestinal epithelium functions as a selective barrier, regulating the passage of antigens, bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS), and other microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) into the portal circulation. Dysbiotic microbial communities may produce altered SCFA ratios, reduced mucus-layer-supporting bacteria, or increased LPS-producing gram-negative bacteria, contributing to a state termed "leaky gut" characterised by increased paracellular permeability.

Elevated circulating LPS is associated with low-grade endotoxemia and systemic inflammation, which can impair glucose homeostasis, reduce insulin sensitivity, and promote a pro-inflammatory metabolic phenotype. Studies in rodent obesity models demonstrate that microbial-derived LPS translocation precedes weight gain and metabolic dysfunction, suggesting a causal pathway. In humans, markers of LPS translocation correlate with measures of insulin resistance and weight gain, though prospective intervention studies are limited.

SCFA, particularly butyrate, reinforce tight junction integrity and modulate intestinal immune responses, suggesting a protective mechanism through which fermentation-competent microbiota may maintain barrier function and limit endotoxin translocation.

Dietary Influences on Microbial Diversity

Diet is a primary determinant of microbial community composition. Plant-based dietary components, particularly dietary fibre and polyphenols, selectively promote the growth of specific bacterial taxa and increase overall microbial richness and evenness—hallmarks of a "healthy" microbiota.

Soluble fibres (inulin, pectin, beta-glucans) and resistant starches are readily fermented by commensals, generating elevated SCFA concentrations. Polyphenol-rich foods (berries, legumes, tea, nuts) serve as substrates for bacterial metabolism and possess antimicrobial properties that shape community composition. In contrast, diets high in refined carbohydrates, saturated fat, and processed foods typically support reduced bacterial diversity and altered community composition characterised by reduced SCFA producers.

Short-term dietary interventions demonstrate rapid shifts in microbial composition following changes in fibre and polyphenol intake, highlighting the plasticity of the microbiota and the direct influence of dietary choice on this ecosystem.

Gut–Brain Axis in Energy Regulation

The gut-brain axis encompasses bidirectional signalling between the enteric nervous system, intestinal epithelium, and central nervous system. The vagus nerve transmits signals from gastrointestinal chemoreceptors and mechanoreceptors, including those sensitive to SCFA, to brainstem nuclei involved in appetite control and energy homeostasis. Enteroendocrine cells release hormones such as GLP-1 and PYY in response to microbial metabolites and dietary components, signalling satiety to hypothalamic feeding centres.

Dysbiotic microbiota produce altered SCFA profiles and may alter the expression or sensitivity of SCFA receptors on enteroendocrine cells, potentially impairing the signalling capacity of appetite-suppressing hormones. This mechanism is hypothesised to contribute to dysregulated energy intake and positive energy balance. Conversely, interventions that restore SCFA-producing bacteria and increase SCFA production may enhance satiety signalling and promote negative energy balance.

Neuroimaging and neurophysiological studies demonstrate that microbial dysbiosis is associated with altered functional connectivity within central appetite-regulating networks, suggesting structural or functional neural remodelling linked to microbiota composition.

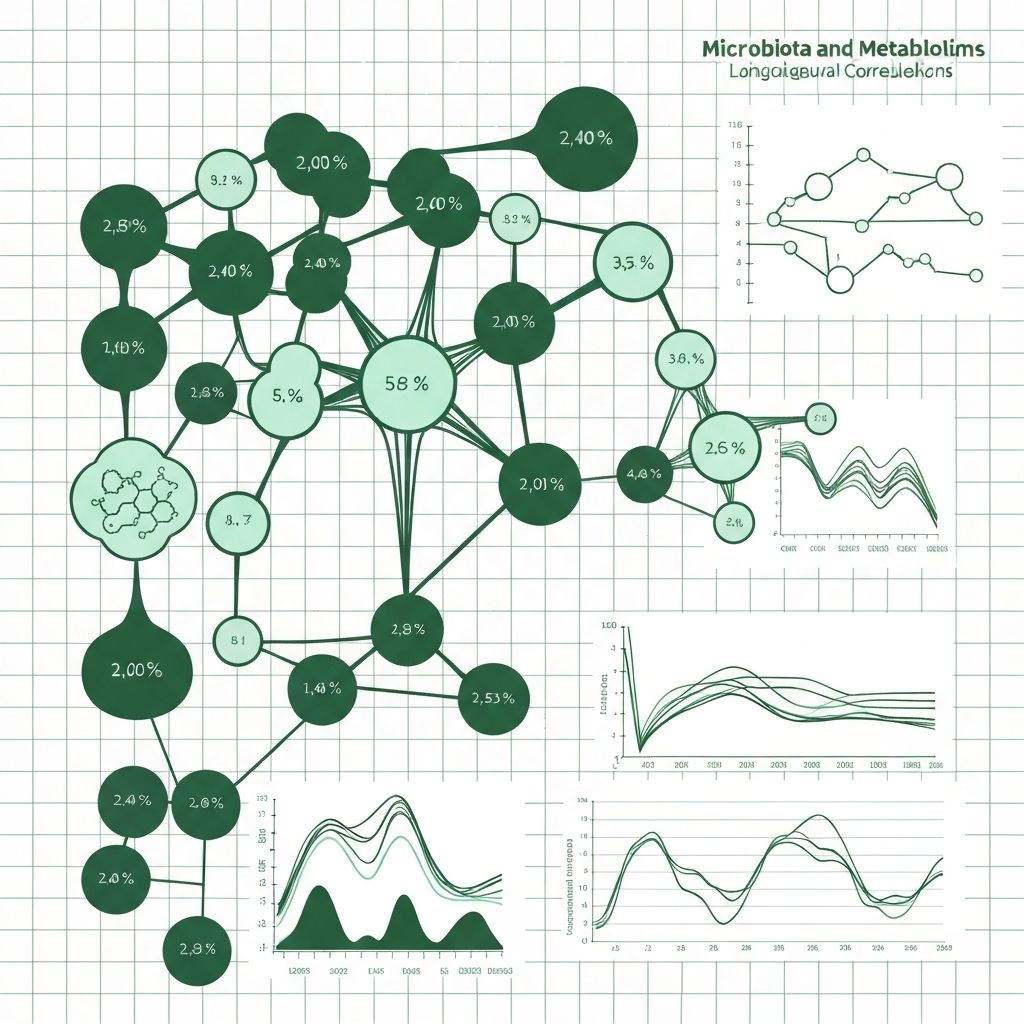

Longitudinal and Cross-Sectional Study Findings

Numerous large-scale epidemiological studies have documented associations between microbial diversity metrics, specific bacterial taxa, and measures of body weight and metabolic health. Meta-analyses have identified consistent patterns—such as reduced alpha diversity and altered Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratios in obese populations—yet effect sizes are typically modest, and substantial heterogeneity exists across studies.

Longitudinal investigations reveal that microbial changes precede and accompany weight loss in response to dietary intervention or bariatric surgery, with certain taxa predicting weight loss success. However, identical microbial interventions produce variable outcomes across individuals, suggesting that host genetics, baseline metabolic state, and dietary context modulate the relationship between microbiota and weight dynamics.

Mendelian randomization studies and animal model evidence suggest bidirectional causality, wherein dysbiotic microbiota impair metabolic regulation (promoting weight gain), and weight gain alters microbiota composition through changes in intestinal pH, bile acid metabolism, and food intake patterns. The relative contribution of microbiota-driven versus diet-driven weight gain remains unresolved.

Explore Detailed Research Topics

The following articles provide in-depth examination of key mechanisms and evidence linking gut microbiota composition to metabolic regulation and body weight.

Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Their Metabolic Signalling Roles

Detailed exploration of SCFA production, absorption, systemic distribution, and mechanisms of action on appetite hormones and energy metabolism.

Read the article →Gut Microbiota Composition in Lean vs Obese Individuals

Comparative analysis of observational research on microbial diversity, phylogenetic markers, and taxonomic differences across body weight categories.

Read the article →Gut Permeability and Metabolic Endotoxemia

Examination of intestinal barrier dysfunction, LPS translocation, and inflammatory pathways linking dysbiosis to metabolic disease.

Read the article →Dietary Substrates Shaping Microbial Diversity

Analysis of fibre types, polyphenols, and dietary patterns as selective pressures on microbial community assembly and metabolic capacity.

Read the article →Gut–Brain Communication in Energy Homeostasis

Overview of vagal signalling, enteroendocrine cell signalling, and central nervous system integration of microbiota-derived signals.

Read the article →Longitudinal Studies on Microbiota and Body Weight Changes

Summary of prospective investigations on microbiota dynamics during weight loss, weight gain, and metabolic transitions.

Read the article →Common Research Limitations

Whilst evidence supports associations between microbiota composition and body weight variation, significant limitations constrain inference regarding causality and clinical relevance.

Cross-sectional studies cannot establish direction of effect. Reverse causality—wherein weight gain drives microbiota change—remains plausible. Ecological confounding is substantial; individuals differing in weight vary in diet, physical activity, medication use, and socioeconomic factors that directly influence both microbiota and metabolism independently.

Measurement heterogeneity across studies complicates meta-analytic synthesis. Different sequencing technologies, analytical pipelines, and taxonomic classifications yield non-comparable datasets. Reproducibility of specific taxonomic associations remains modest; many findings from small studies fail to replicate in larger cohorts.

Extrapolation from rodent models to humans is limited by fundamental differences in diet, microbiota composition, and metabolic physiology. Intervention studies in humans are few, often small, and heterogeneous in design, limiting generalizable evidence for microbiota-targeted interventions.

Frequently Asked Questions

The F/B ratio compares the relative abundance of two dominant bacterial phyla. Some studies report elevated F/B ratios in obese individuals, hypothesising that Firmicutes are more efficient at extracting energy from dietary substrates. However, this finding is inconsistent across populations, and the ecological significance of this single metric is debated. More nuanced measures of community composition and metabolic capacity may be more informative than any single ratio.

Probiotics and prebiotics may modulate microbiota composition and SCFA production in research settings. However, human intervention trials show variable results, with modest effect sizes on weight loss. Efficacy likely depends on baseline microbiota composition, specific probiotic strains, prebiotic type, individual host genetics, and overall dietary pattern. Current evidence does not support probiotics or prebiotics as standalone interventions for weight management.

Microbial community composition can shift measurably within days to weeks following dietary change. Short-term alterations in relative abundance of specific taxa occur rapidly. However, stabilisation of new community structure and functional capacity requires longer timescales (weeks to months). Reversibility of these changes upon dietary reversion is documented, emphasising the dynamic and plastic nature of the microbiota.

Evidence suggests bidirectional causality. Dysbiotic microbiota may impair energy harvest efficiency, increase intestinal permeability, promote low-grade inflammation, and dysregulate appetite signalling—all pathways potentially contributing to weight gain. Conversely, weight gain alters the intestinal environment (pH, transit time, bile acid metabolism) and dietary intake patterns, reshaping the microbiota. Disentangling primary and secondary effects requires prospective studies and causal inference frameworks.

Increased intestinal permeability ("leaky gut") permits translocation of bacterial LPS into portal circulation, triggering systemic endotoxemia and inflammation. This pathway impairs glucose homeostasis, reduces insulin sensitivity, and may promote a pro-inflammatory metabolic state. SCFA, particularly butyrate, strengthen tight junction integrity, suggesting a protective mechanism wherein SCFA-producing microbiota maintain barrier function and limit pathogenic inflammation.

SCFA activate receptors on intestinal enteroendocrine cells, promoting release of satiety hormones GLP-1 and PYY. Dysbiotic microbiota produce altered SCFA profiles, potentially impairing satiety signalling and contributing to dysregulated energy intake. The vagus nerve transmits signals from SCFA-sensitive chemoreceptors to appetite-regulating brainstem regions. Evidence from animal models supports this pathway; human evidence remains preliminary and inconsistently replicable.

Explore the Science of Microbiota and Metabolism

This resource provides an evidence-based overview of mechanisms linking gut microbiota composition to metabolic processes. Delve deeper into specific topics, research findings, and the current state of scientific understanding.

Continue to Research Articles